Almost everyone who studies or joins meetings takes notes. Good notes help you encode ideas, organize material, spot associations, and draw attention to what matters.

Research shows the longer the session, the more notes matter.

But few people learn how to take them well.

Conventional Notes: Neat but Inefficient

Most people start by writing full sentences, later shortening them with symbols or underlining. The notes look tidy but slow the mind.

While you write one phrase, the next idea slips away.

You waste effort copying words instead of capturing meaning.

Figure 1. Conventional linear notes: neat but memory-unfriendly (Source — Fly_Boy_01 / Reddit).

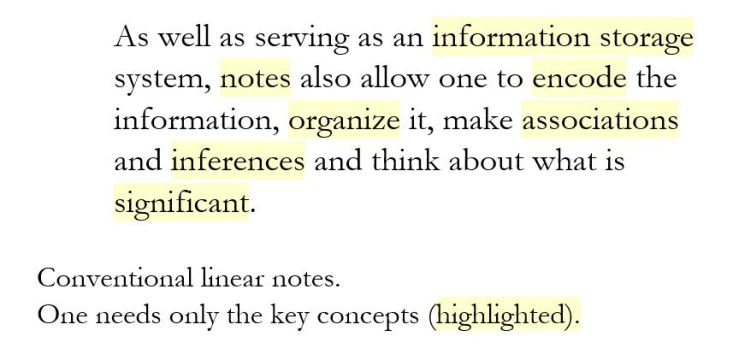

Key Words Change Everything

Words differ in power. Some carry vivid meaning or emotion; others merely fill space.

When you read, your mind automatically grabs the strong ones and forgets the rest within seconds.

Example:

“Astronomers now suggest that black holes may not be entirely black but may radiate energy.”

The memory anchors on astronomers, black holes, not black, radiating energy—the rest only serves grammar.

Concrete words trigger mental images faster than abstract ones.

At Exeter University, Michael Howe found students who filled their notes with key words recalled far more. Key words “lock up” ideas; recall them, and the full meaning returns.

Children begin speech with key words—“John ball,” “Susan tired.”

Early languages worked the same way: Latin folded connectors into endings; Sanskrit used almost nothing but key words.

They communicated richly without waste.

Figure 2. We recall the circled key words, not the filler around them (from The Brain Book, Peter Russell).

Why the Brain Favors Association

The brain never thinks in straight lines.

A computer steps through logic; the brain leaps—linking ideas, hearing tone, reading faces, and comparing patterns all at once.

Every word sparks dozens of associations. Write down one—tree—and your mind flashes forest, roots, shade, family, growth. No two people form the same network.

Creative writing thrives on this branching energy; scientific writing disciplines it.

Learning and remembering flourish when we honor the associative mode.

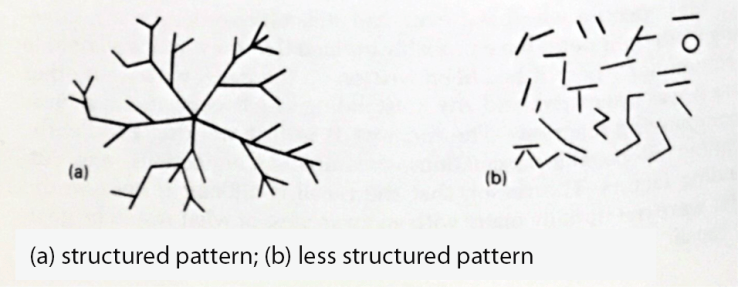

Mind Mapping: Thought That Branches

Linear notes flatten meaning.

Mind mapping restores the brain’s natural rhythm by combining organization, association, and imagery.

Start in the center of the page with a vivid image or word.

Let main branches radiate outward, each carrying a key word, picture, or symbol that triggers related ideas.

The map grows like a living tree—connected, flexible, and easy to recall.

Figure 3. Organized versus scattered mapping—structure creates memory links (from The Brain Book, Peter Russell).

Building an Effective Map

Organize. Build visible structure. Place each idea where it fits and connect it to others.

Use Key Words. Capture essence, not filler; each key word unlocks a chain of thought.

Cluster. Limit main branches to about seven or eight, each with smaller offshoots—just right for working memory.

Add Association. Link ideas with arrows or color; connection fuels recall.

Think Visually. Print clearly along lines, use colors and small drawings to engage both hemispheres.

Make It Stand Out. Vary color, size, and shape; what stands out sticks.

Stay Active. Keep the mind moving—add humor, sketch ideas as they arise, explore connections fast.

Mind maps grow as quickly as thought itself, turning the brain’s love of connection into visible understanding.

Advantages of Mind Mapping

- Mind maps mirror the way memory links ideas.

- The mind recalls key words and images, not sentences—maps match that pattern.

- A page can hold far more information because you remove filler.

- Review comes quickly; each glance re-triggers full meaning.

- Starting from the page center lets you branch freely in any direction.

- Visual qualities—color, placement, uniqueness—make recall easy.

Where to Use Mind Maps

Use mind maps whenever ideas flow in or out of your head.

Learning and Taking In Information

Record books, lectures, meetings, or calls as branching patterns, not lines. The map organizes as your brain does—associatively—so recall strengthens naturally.

Reviewing and Remembering

Mind maps let you review quickly. Studies show recall rises about 50 percent compared with prose notes. Review right after you draw the map, again the next day, a month later, and six months later—the rhythm that locks memory.

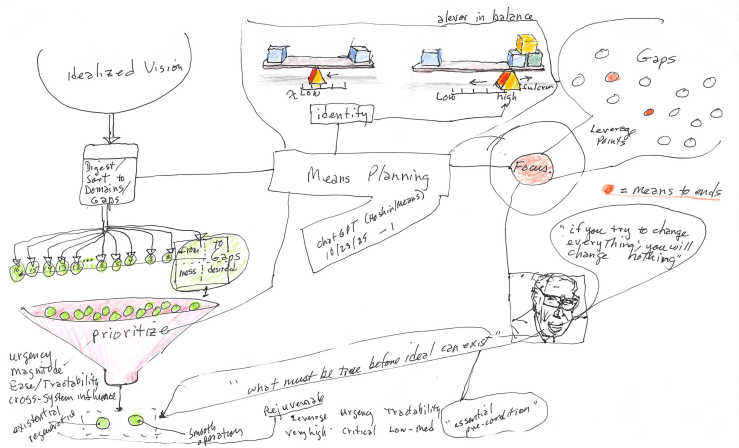

Creating and Planning

Each branch sparks new ideas. Mind maps accelerate brainstorming, problem-solving, and project planning. Build first, order later—no shuffling lists.

Presenting or Facilitating

Display main branches while you speak. The audience follows your logic; you stay oriented.

Writing and Designing

Large works—books, talks, reports—grow faster from a set of mind maps. Draft freely, then convert to linear text when ready.

Mind maps serve anywhere thought moves—gathering ideas or sending them out.

Try It Yourself

Everyone’s maps differ.

They may not make sense to others, but they will fit you.

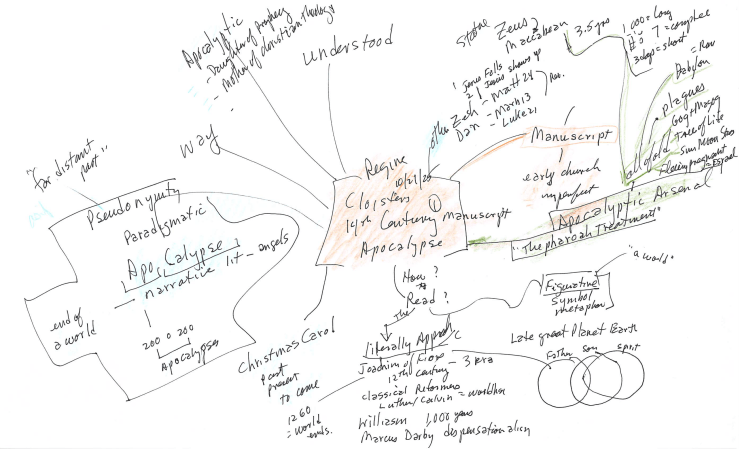

Figures 4–6. My own mind maps—different styles for study, lectures, and review.

Sometimes I capture key concepts slowly, adding drawings that help me see connections.

Sometimes I race to keep up with a lecture—neatness drops but energy rises.

Other times I take the time to reinforce a few central insights.

Each map fits its moment.

The Master Map

Before long, you’ll invent your own style, but it helps to see a full professional model.

Figure 7. Peter Russell’s complete Mind Map on Note Taking and the Rules of Mind Mapping (from The Brain Book).

This single image contains the whole method—key words, color, structure, association, and playfulness—all working together.

They Work!

I’ve used mind mapping for forty years.

It shaped how I learn, facilitate, plan, and create.

Each map feels like a living record of thought—half art, half architecture.

Try one page; your first attempt will already show how naturally your mind thinks this way.

You’ll soon feel how memory wakes up when ideas branch instead of march.

Credits

Based on ideas and figures from The Brain Book by Peter Russell.

Additional images: Fly_Boy_01 (Reddit) and the author’s own examples.